Configuration Management Across Multi-Site Aerospace & Defense Suppliers - Part 1

After our last post on the Challenges of Implementing Configuration Management, a reader asked if the obstacles to successfully deploying configuration management were very different between a modest-size single-production facility versus a large multi-national multi-site enterprise. An example of the former in the Aerospace & Defense industry is a Tier 3 component part manufacturer, while the latter is a global Tier 1 aerostructures supplier.

Our answer was both “No” and “Yes.”

No, in CMstat’s experience the obstacles, when you dig deep enough, at their very core are not all that different. However, they can manifest themselves in different ways to appear on the surface as if they are quite unique.

So yes, the risks and costs are more visible and magnified with large multi-site suppliers, thus the consequences may seem very different. This can lead some to conclude that the underlying configuration management requirements and deloyment challenges must also be very different. But rarely is this true.

The Constantly Revolving A&D Supply Chain Landscape

CMstat’s relevant experience extends from delivering configuration management consulting services and configuration management software, like PDMPlus and EPOCH CM, within OEMs and Tier 1-3 suppliers in the Aerospace & Defense industry over a span of three decades. During this time, we have watched OEMs spin off their own vertically-integrated manufacturing facilities to supply chain conglomerates, largely to the initial delight of financial markets and private equity investors.

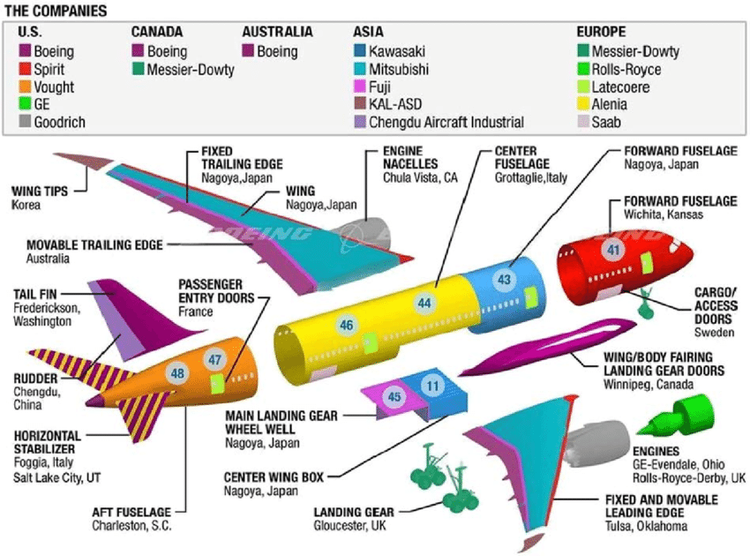

Aviation Industry Example of Global Supply Chain Partners for 787 Dreamliner Program - Image of The Boeing Company

Then a few years later, many OEMs were confronted by a decision to either fire or buy back their supply chain partners when things did not work out as planned either on the final assembly line or in the quarterly financial analyst calls. This was especially true when the supplier failed to deliver on schedule, slowing down an entire program, or when they did deliver on time their profit margins proved superior to those of the OEM. There are numerous examples of both occurrences in the A&D industry business press, including those referenced by Kevin Michaels in his commentaries on the evolution of the aerospace supply chain.

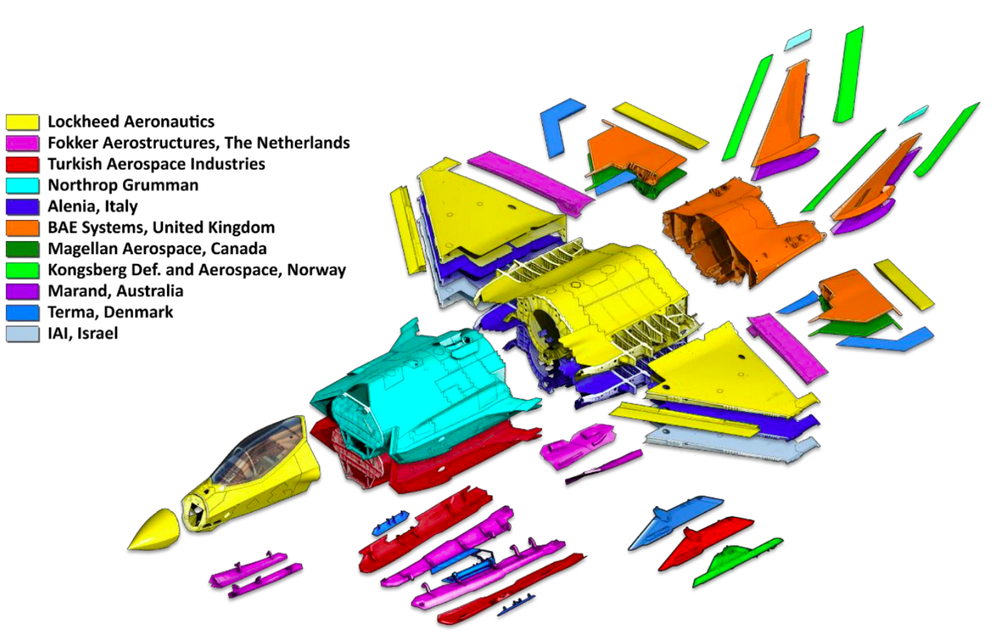

Aerospace & Defense Industry Example of Global Supply Chain Partners for F-35 Fighter - Image of AIAA ARC

The underlying business and technical problems which contributed to these supply chain problems were numerous and many of them should have been predictable. More than a few include the lack of effective configuration management and change control across the supply chain, of which several colossal foul-ups have also been well documented.

Deploying configuration management and enforcing change control processes for increasingly sophisticated equipment within a wholly-owned vertically-integrated manufacturer is tough enough. The complexity and cost of doing so for an entire aircraft or weapons system across companies and borders is often grossly underestimated.

As example, the process of change impact analysis is unwieldy enough within the same organization. It is often beyond the capacity of even the best-in-class firms to conduct a what-if analysis of a proposed change that extends across a multi-tiered international supply chain. The digital thread, if one exists, often gets lost into a digital black hole. No one office ends up with a complete view of a proposed change as has been written about by CM specialist Martijn Dullaart in his blog The Future of CM.

Challenges Few Suppliers Admit to Having and OEMs Pretend Don’t Exist

CMstat’s consulting clients have included large multi-national firms with their own facilities and suppliers spread across the globe, typically supporting several program contracts at one time. Other customers have been smaller production, sustainment or maintenance sites supporting just a few customers and products.

Over the years of our work we have heard a number of challenges voiced directly by our clients, or deciphered indirectly from what they were not willing to say. Here are a few of the most frequent observations:

While some multi-national suppliers may have an enterprise-wide vision and mandate for PLM, PDM, CM, and DM, many sites maintain relative autonomy for their legacy systems. It’s often for good reason because the mandate from afar did not fully incorporate each site’s unique business priorities and technical requirements.

As a general rule, Tier 1/2 managers have less appreciation of the role of Configuration Management when compared to their OEM peers. As a result, they underestimate the investment in people and skills that will be needed to support a contract.

The responsibility for administering CM can vary greatly within a supplier’s organization to include positions in contracts, engineering, manufacturing, procurement, logistics, and quality. Often, no one office feels total responsibility and thus lacks the authority needed.

For suppliers with multiple sites, each location is almost always found to be operating at different stages of their CM implementation with different levels of CM maturity, and more importantly, different levels of awareness of these gaps.

The individuals responsible for oversight of CM will possess varying levels of education, experience, training, certification (if any) and professional motivation. They will also receive differing levels of support and enthusiasm from their managers for continuing education and professional development.

Executives within Tier 1/2 suppliers often see little short-term financial upside to invest outside of the manufacturing floor, where profits are made, in developing core capabilities like CM, where profits can be lost. They are not entirely wrong as the Return-on-Investment calculations rarely include a Cost-of-Failure term.

Often the financial business model and capitalization of suppliers simply does not allow them to make the same long-term investments in people or technology that OEMs are capable of doing, despite OEMs assuming or expecting this of their suppliers.

This reality is especially evident for those suppliers who serve multiple OEMs, each with different PLM, PDM, BOM, and CM processes and supporting software. As a result, sites serving multiple customers, programs and product lines encounter a labyrinth of different CM requirements, change control policies, and data management procedures, most of which are poorly documented and communicated.

(Spoiler alert to OEMs who remain in denial.) It is not uncommon that each individual supplier site resorts to developing their own set of BOMs for the same contract due to differences in equipment, materials, processes, and their own in-country Tier 3 suppliers. Occasionally, they will do so out of sheer necessity such that their production rates are not held hostage by a stream of data sets which they cannot control.

Alternate procedures, part numbers, substitutions, phantom parts, and configuration variants become unique to each subcontractor site with reduced or non-existent visibility to the OEM. This has left more than one OEM logistics manager to ask who thought it was a brilliant idea to outsource build, much less design, authority of mission-critical components.

OEMs keep pushing out engineering change notices and updated BOMs to their suppliers, often with little explanatory context or bidirectional coordination, leaving each one subject to interpretation and prioritization. Insufficient notification causes suppliers to work backwards after the receipt of new product data rather than planning for it earlier in the change process.

Supply chain partners often lack the capability to account for changes in requirements and assign costs that can be charged back to their OEM customers. This results in even greater financial stress on a program, reducing the capacity to invest in CM as budget leaks out of the program.

Instead of developing their own quality control requirements and procedures, some contractors rely upon only the OEM-provided documentation for approvals. While this is certainly necessary, it is rarely sufficient to meet all the quality assurance expectations.

Lastly, for suppliers that operate across multiple nationalities, differences due to international cultures, even within the same corporate business culture, can never be taken for granted. These differences will include communication styles, conflict resolution, authority power dynamics, risk/uncertainty avoidance, and performance motivations. Cultural differences are submerged mines that can explode to the surface when there are inevitable mistakes, delays, or failures.

Having a Multi-Site Plan for CM is Not the Same as Having a CM Plan for Multiple Sites

How can these problems be avoided or challenges mitigated for suppliers to provide a consistently produced product?

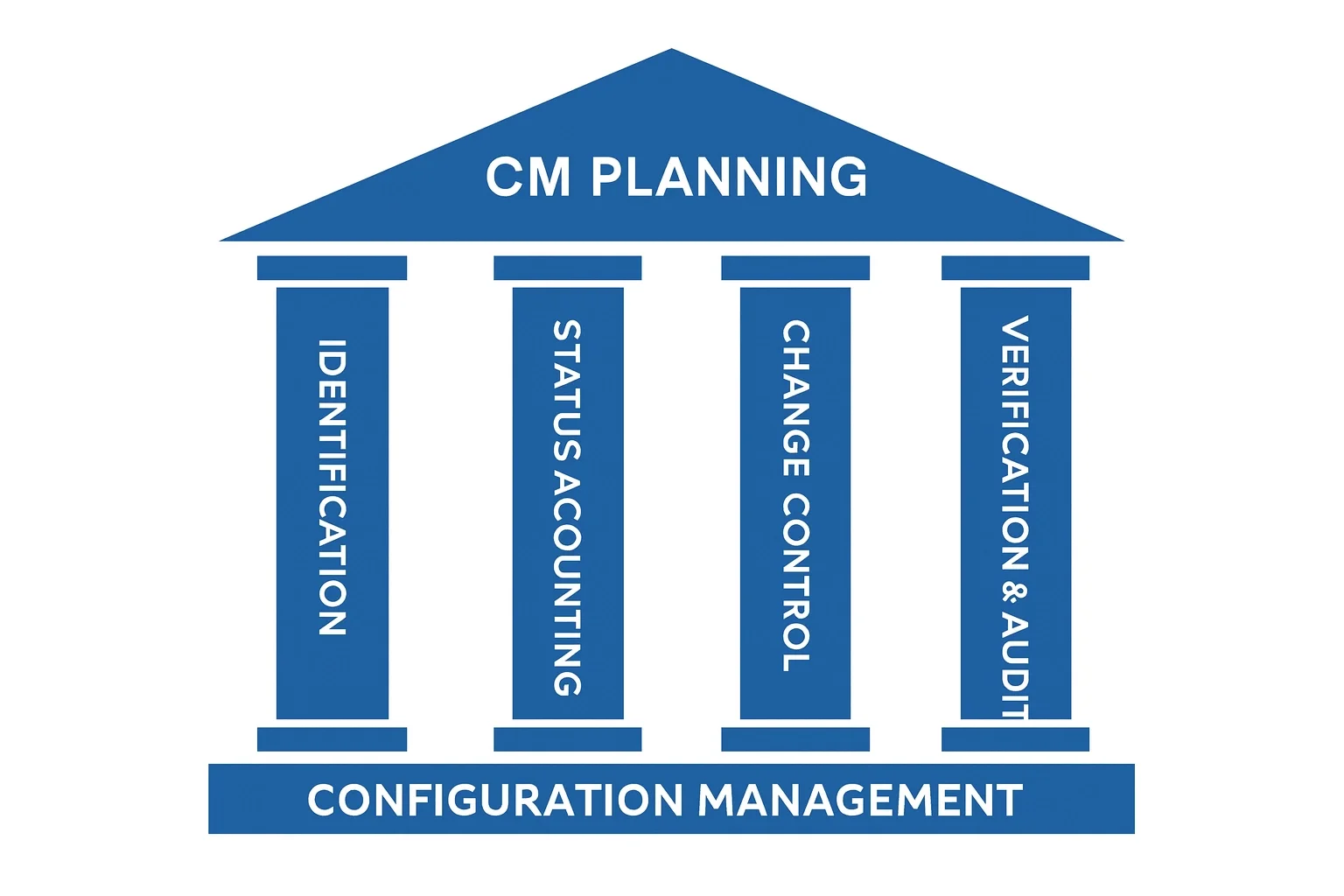

In our experience, all can be effectively dealt with by implementing an appropriate, comprehensive Configuration Management Plan. By appropriate, we mean a plan that is written and customized for the enterprise, including all of its programs and sites, and is not a generic off-the-shelf template. By comprehensive, we mean incorporating the five foundational elements of configuration planning, configuration identification, change control implementation and verification, configuration status accounting, and configuration traceability and audit.

These CM fundamentals are equally valid for small Tier 3 component sites and large Tier 1 multi-nationals alike. This is due to the intrinsic strength in the robust range of applicability of CM standards and certification programs developed over the years by organizations like CMPIC and IpX along with all those they have trained.

The greatest difference in execution will be in the weight factor that each fundamental element deserves. With multiple-sites deployments, the stage of CM planning is much more consuming, as it should be.

To correctly implement all elements of CM, a configuration management plan should be developed, reviewed, approved, and then accepted by all stakeholders in a process that can take months. Admittedly, it is not easy to convince a contract office to make the investment in time and money to do so when the schedule and budgets have likely already been set. And to do this across a supply chain is most certainly not an easy task.

In the next post in this series, we’ll be examining in more detail the most important elements in a plan for deploying configuration management across multi-site A&D suppliers. This will include our own recommendations from lessons learned by ourselves and our clients.

One such topic will be the best practice to have a resilient CM Plan that can survive and evolve as requirements change in contracts, suppliers, products, and materials. This does not mean sacrificing specificity in the plan to make it so vague that it can adapt to whatever may happen in the future. Instead, it means incorporating well-defined performance metrics and feedback processes in the original plan which can lead to continuous process improvements driven by a living plan that is not shelved after the implementation.

To receive notices of future CMsights posts be sure to subscribe to CMsights then follow CMstat on LinkedIn.

Receive CMsights

Subscribe to CMsights News for the latest updates from CMstat on Configuration Management, Data Management, EPOCH CM, and EPOCH DM.

Request a Demo

See how EPOCH CM and EPOCH DM support industry standards and best practices in Configuration Management and Data Management.